The Origin of Tahuantinsuyo: Myths and Migrations

The origin of the Tahuantinsuyo is surrounded by myths and legends. According to the traditional story, after the Huari hegemony and the migratory movements in search of fertile lands, Ayar Manco, or Manco Capac, arrived in the Cusco valley. There, the ayllus or clans settled after confronting the curacazgo of the Ayarmaca. This settlement is narrated in the legend of the Ayar brothers, which tells how Ayar Manco, along with his brothers Ayar Uchu, Ayar Cachi and Ayar Auca, set out on a journey from Pacaritambo, a sacred cave in the Tamputoco hill. In his search for a place to settle, his brothers succumbed to various situations, leaving Ayar Manco as the leader who would lead his people to the valley of Acamama, where they founded Cusco. This period, known as the Curacal Period, marks the beginning of the domain that would become Tahuantinsuyo.

Social Organization and Hierarchy of the Inca Empire:

Tahuantinsuyo society was characterized by a hierarchical and rigid structure. The Sapa Inca, considered a descendant of the Sun God, was the highest authority and had as a symbol of power the Mascaipacha, a red tassel on his forehead. His successor, the Auqui, was not necessarily the eldest son, but the most capable, according to the choice of the Inca and the consensus of the nobility. The Tahuantinsuyo was organized in ayllus, which were family clans with a strong bond of kinship and mutual responsibility. The ayllus were led by curacas, who responded to the orders of the Sapa Inca and coordinated communal work, such as infrastructure construction and agriculture. These clans were rooted to the territory and could only move by imperial mandate, such as the mitimaes, who were relocated for strategic purposes. On the other hand, the panacas, noble families of the Inca, had an essential role in the preservation of memory and lineage, which cemented the authority and stability of the dynasty.

Economic Structure: Reciprocity, Agriculture and Livestock

The Tahuantinsuyo economy was fundamentally agricultural and was based on principles of reciprocity and redistribution. Land was divided into three types: the lands of the Inca, the lands of the Sun and the lands of the ayllus. Each plot was destined for different purposes, such as the maintenance of the temples and the sustenance of the nobility and the population. To maximize agricultural production, the Incas built advanced hydraulic engineering works, such as canals and terraces or platforms, which facilitated irrigation and agriculture on high ground. They practiced innovative agricultural methods, growing a wide variety of crops such as potatoes, corn and quinoa. Livestock also played an important role: the llama and alpaca were domesticated for transport, wool and, occasionally, for sacrifice in religious ceremonies.

In addition, the Tahuantinsuyo had various forms of community work: the Ayni, a system of mutual aid in which members of an ayllu collaborated in agricultural work or in the construction of houses; the Minca, a compulsory work for the benefit of the ayllu; and the Mita, a labor system where men between 18 and 50 years of age worked for the State in the construction of infrastructure and the production of goods. This economy sustained the large population and allowed the Sapa Inca to redistribute resources in times of scarcity.

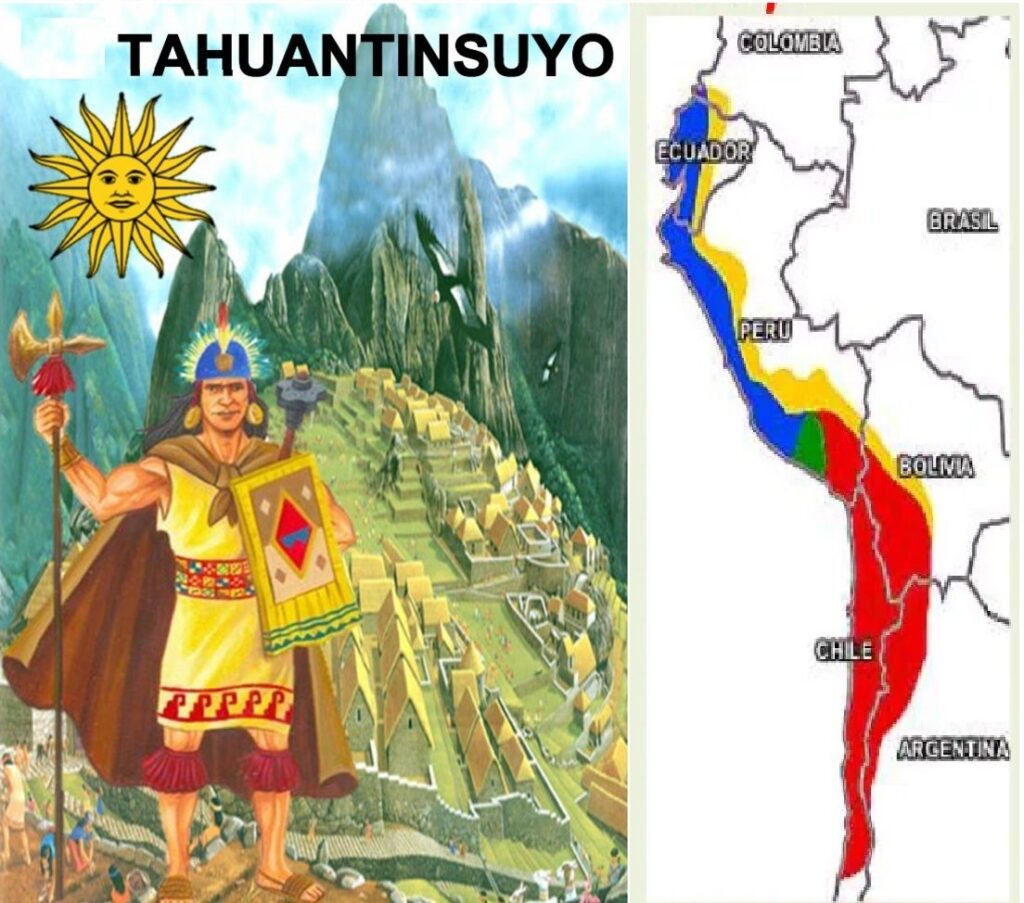

The Four Regions of the Tahuantinsuyo and their significance

The division of Tahuantinsuyo into four suyos, or regions, reflected not only the administrative organization of the empire, but also the Inca worldview. Each suyos had a strategic role in the economy and culture of the empire:

-Chinchaysuyo: the most populous and productive region, northwest of Cusco, which encompassed present-day territories of Ecuador and part of Peru.

-Antisuyo: to the east of Cusco, comprising the Amazon, a region rich in natural resources and exotic products.

-Contisuyo: to the southwest of Cusco, with vast territories up to the Pacific coast.

-Collasuyo: to the south of Cusco, comprising areas of Bolivia and northern Argentina and Chile, known for its production of llamas and alpacas.

This division, in addition to facilitating the administration of the extensive empire, reinforced the control and collective identity around the capital Cusco.

Religion and Inca Cosmovision in the Tahuantinsuyo:

Religion was central to the life of the Tahuantinsuyo, where the Sapa Inca was seen as the son of the Sun God (Inti), the most revered in the divine hierarchy. The Incas believed in a universe divided into three worlds: the Hanan Pacha (world of the gods), the Kay Pacha (world of the living) and the Ucu Pacha (subway world of the dead). Other important gods included Pachamama (mother earth), Illapa (god of lightning) and Pachacámac (god of earthquakes).

Inca religion included ceremonies and rituals in which offerings were offered, including llama and occasionally human sacrifices. Inti Raymi, the feast of the Sun, was the most important festival, and the Huillac Umu, the high priest, officiated at the ceremonies. The role of religion was not only spiritual, but also political, as it reinforced the authority of the Sapa Inca and social cohesion.

Education and Transmission of Knowledge in the Inca Society:

Education in the Tahuantinsuyo was elitist and was imparted in the Yachayhuasi, or “House of Knowledge”, where the children of the nobility were instructed by the amautas in religion, administration and defense of the empire. These young men culminated their education with the Huarachicuy, a ceremony that prepared them to assume their responsibilities. Noble and village women, chosen for their beauty and skills, were educated in the Acllahuasi, or “House of the Chosen”, where they learned to weave, perform artistic activities and, in some cases, became secondary wives of the Inca or virgins of the Sun.

Infrastructure and Architecture: From the Qhapaq Ñan to Machu Picchu:

Inca architecture is one of the most outstanding of pre-Columbian times, characterized by the use of polished stones assembled without mortar, which have resisted the passage of time and earthquakes. Constructions such as Machu Picchu, Pisac and Sacsayhuaman show their mastery. In addition, the Tahuantinsuyo developed a vast network of roads called Qhapaq Ñan, which linked the entire empire, facilitating the transportation of goods and territorial administration. This road system, with more than 30,000 kilometers of roads, connected the capital with the most distant places and allowed for rapid communication.

The Decline of the Tahuantinsuyo: Internal Conflicts and the Spanish Conquest:

The Tahuantinsuyo began its decline with the civil war between Huáscar and Atahualpa, the sons of the Inca Huayna Cápac, who disputed the succession. The war weakened the empire and paved the way for the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro in 1532. After capturing and executing Atahualpa, the Spaniards took Cusco and, with it, disintegrated the Tahuantinsuyo. The destruction of temples and quipus during the Spanish conquest erased much of Inca history and culture.

Legacy of the Tahuantinsuyo in Contemporary Andean Culture:

Today, the legacy of Tahuantinsuyo is still present in Andean culture. Customs such as the Inti Raymi celebrations, the use of Quechua and Andean agricultural techniques are legacies that keep alive the identity of the peoples that were part of the Tahuantinsuyo. The architecture and textiles, among other elements, reflect the ingenuity and cultural richness of the empire. The Tahuantinsuyo not only represents a past civilization, but a source of pride and historical connection for millions of people in South America.